11:09 AM

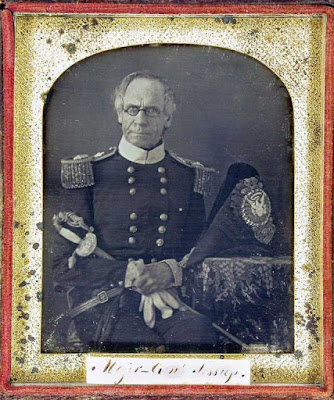

Above- Daguerreotype of Major General Jessup. ca. 1847-1848 (Mexican War). During 1855, he was the Head of the Dept of the West.

While I am working on my revising my Salesman’s Journal visit to Boston, I am posting an article I wrote for the Military Collector & Historian Journal Vol. 49 Vol. 2 Summer 1997 titled, Ft Pierre Sutlery 1855.

Steamboat Arabia was one of six steamboats contracted to bring troops and provisions to establish the fort Pierre. Fort Pierre served as the “central office” for several other forts.

Steamboat Arabia was one of six steamboats contracted to bring troops and provisions to establish the fort Pierre. Fort Pierre served as the “central office” for several other forts.

At the time Steamboat Arabia's contract was drawn up, Arabia's owner, Capt John Shaw, was not present. It was Robert Campbell, a wealthy St. Louis businessman and Indian agent, who negotiated and signed Arabia’s contract to transport troops & supplies to Ft Pierre. (See how primary source documents bring out the bigger picture?)

This was my first experience with publishing an article. I learned when writing for a publication, not everything I wanted to say could be printed. Otherwise, this 9 page article would have been a 300 page one! The Steamboat Arabia Museum’s curator Greg Hawley told me they received many copies of my article and he laughed saying,

“They think we don’t know who you are!”

I thank the editorial staff and especially Fred Gaede for being patient with me during the 4 months of correspondence. Besides the errors in grammar, I had numerous questions from the editorial staff. One asked, “Why was Ft. Pierre chosen to store the inventory when steamboats passed another fort further down river?” The query made complete sense to me and original I said, the documentation says so, but today a more street wise historian -all I can say is the word, “Politics”.

Enjoy this article- it is only the top of the ice berg and a good foundation for revealing the other stories you’ll read in later postings.

TO ENLARGE THE ARTICLE BELOW-

PRESS THE CTRL KEY AND THE + KEY AT THE SAME TIME.

TO RETURN TO THE ORIGINAL SIZE PRESS THE CTRL KEY AND ZERO KEY

TO RETURN TO THE ORIGINAL SIZE PRESS THE CTRL KEY AND ZERO KEY

Ft Pierre Sutlery, 1855 Elizabeth Soderberg

In 1855, Pierre Chouteau, Jr. of the American Fur Company sold one of his posts, Fort Pierre, in Nebraska Territory (presently South Dakota) to the U.S. Government for S45,000.The fort was intended to be a central depot circled by other outposts (Forts Laramie, Kearney, Union and Randall). The overall purpose was to protect emigrant routes leading from the Missouri River to the West from Indian hostilities. Fort Pierre was located on the west side of the Missouri, near the mouth of the Bad (Teton) River. It was soon realized that a more northern outpost would be needed, one that provided better timber than cottonwood. In 1857, Fort Pierre was abandoned and its salvageable building materials were used at Fort Randall.

During the months of May through August 1855, Port Pierre was provisioned for the soldiers of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. This article will focus on the establishment of the first sutlery, operated by Edward G. Atkinson, who was a partner of the St. Louis firm of Frost & Atkinson. Bank ledgers in the papers of the St. Louis fur trade verify purchases were made on a credit basis, which was a common practice. As with all post sutlers, Atkinson was authorized to provide much of what the quartermaster or subsistence departments did not. Further, at least in theory, he was required to ensure that a variety of affordable goods was available to the soldiers and their

families.

families.

The task of moving supplies to establish a fort on the upper Missouri was costly. Roads were poor and only a few steamboats ventured that far west. During the planning stage, it was determined that six steamboats (two government owned and four contracted) would carry the supplies and troops west. The steamers were the Gray Cloud, William Baird, Arabia, Australia, Kate Swinney and Clara. The Sioux Expedition, as it was called, was planned to begin during the "Spring rise," when the river was at its highest. In St. Louis, Major David H. Vinton, Assistant Quartermaster of the Department of the West, had each steamer equally loaded with a variety of goods so that if one sank the loss would be minimal. The steamers not only had part of the 2nd U.S. Infantry aboard (commissioned officers, band, companies A, B, D, I and G), but also sutlery goods, paying passengers and their freight.

Despite all this planning, there were numerous problems. First, despite the efforts of Thomas Madison, 2nd U.S. Infantry Assistant Surgeon, cholera got aboard the Arabia, causing the deaths of two soldiers. Second, the Missouri River was unusually low and the steamers could not float over the sand bars. In order to continue upriver, they were forced to unload part of their cargo, leave it on the shore, and subsequently return for a second load. On just the Arabia’s contract, this added a cost of $400 a day. Third, snags in the river sank two of the privately owned steamers, Australia and Kate Swinney. The Australia sank on the initial journey to Fort Pierre and the Kate Swinney on its course back to St. Louis. Remarkably, no cargo except the uniforms on the Australia was lost.

The sutlery appears to have goods on at least two of the Steamers, if not all. The goods on the Australia that were lost to the river were insured for $6,779.25, which Frost & Atkinson paid the following wholesalers whom were mostly from St. Louis:

Shapleigh, Day & co. $375.50

Wolf & Hoss $238.86

E. A. & S. R. Filley $218.00

A. H. Shultz $281.79

Martin & Bro $789.38

J. S Watson $357.80

H. &R. B. Whittimore $180.40

Hartnet & Taylor $127.00 2

Fort Pierre could hardly have been considered a bargain. It had been built in 1832 and was previously renovated in the late 1840s. In 1855, when the 2nd. U.S. Infantry regimental assistant quartermaster, Captain Peter T. Turnley, arrived, he found many buildings in great disrepair. It took soldiers six weeks to renovate these structures. Beside s that problem, there were not enough buildings to hold the expected troops.

In anticipation of this problem, the military sent a number of portable cottages on the Gray Cloud, making this one of the first times this innovation was utilized. According to Private Augustus Meyer’s memoir, Ten Years in the Ranks of the U. S.

Army, these buildings were used by the officers and soldiers, as well as for a necessary storehouse on the riverfront. As seen in the sketch by Lieutenant George K. Warren, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (FIG 1), Fort Pierre consisted of 81 buildings the use of which was determined by Captain Turnley. He made assignments to 49 of the buildings.3 The sutlery was assigned one of the largest (70 feet by 30 feet) near the bake houses. By the end of the summer, the fort was fully provisioned and operational.

Once the shelves of the sutlery were stocked, in August 1855 Major (brevet Lieutenant Colonel) William R. Montgomery, regimental commanding officer at Fort Pierre, ordered an inventory prepared of the sutler’s stores. This order was necessary because Indian traders would charge a markup of 100% for the same goods, based on supply and demand. The military viewed this as a hardship for the soldier and therefore Army regulations regarding tariffs were established. These regulations required Montgomery to price all goods at Fort Pierre based on their actual cost and transportation costs. His inventory reveals an incredible variety of goods available on the frontier, and is provided below in its entirety:

[SEE INVENTORY BELOW - AFTER THE NOTES- I'll try OCR again for the inventory]

By the Order of Lieut Col. Montgomery

N M McLean

lst Lieut & Adjt 2nd Inf

Post Adjt 4

Once completed, Atkinson's sutlery was open. It was a general store in every sense of the word, and Private Augustus Meyers of the 2nd U.S. Infantry was a paying customer. He remarks during the season of 1855 and 1856:

“A sutler had established a store, with miscellaneous stock of goods such as soldiers needed, also goods for trading with the Indians. But the prices were so high that we could not afford to buy much. This was due to the high cost of steamboat transportation, which amounted to about fifty dollars per ton from St. Louis. 5

By Meyers’ lack of overwhelming surprise, it would appear that Atkinson was a typical sutler, who sold and bartered with others. Therefore, the immense range of choice was commonplace and met the needs of the soldier. This selection, especially in readymade clothing, is vast (15 types of coats, 28 pants, 19 hats and 9 shirts). The sale of such items as; backgammon sets, books and liquor leads, to the not too surprising conclusion that the garrison troops spent their free hours playing games, reading and drinking.

Selling to Indians and homesteaders was against regulations, but nonetheless it was a common practice. The very long list of women’s and children’s clothing, besides the Indian trade goods present, support the observation that Atkinson served more than just the soldier and his family.

Finally, all who shopped at Atkinson’s sutlery could select from an assortment of canned goods such as lobster, oysters and fruits. Even though expensive ($1.50 each) at a soldier’s pay, this variety demonstrates that Americans were no longer restricted by season or distance from what they relished.

Because sutlers were appointed, there is little documentation about Edward G. Atkinson. What is known about him and how he ran his sutlery is based on letters in the National Archives and in Meyers’ memoir. Atkinson was appointed based on his being a relative of a general (which one exactly is uncertain). Sutlers, by regulations, were required to reside in or near the post. Since there were no buildings outside Fort Pierre, Atkinson probably used the sutlerys’ attic as his family residence while he operated the business down below. This reflects typical business practices of the time.

He and his employees appear to have been disliked by the officers. They cited Atkinson for encouraging loitering, overselling rations of liquor and beef for soldiers, his family and others. Shortly thereafter, he submitted his resignation, which was refused on the grounds that there was no one to replace him. Finally, in November 1856, 2nd U.S. Infantry Captain Christopher S. Lovell notified Secretary of War Jefferson Davis that there was to be a change in sutlers at Fort Pierre and that he had appointed M.W. Leigh Wickham. Overall, Edward G. Atkinson did provide a variety of goods and sold them for what was considered a reasonable price. In doing so, he also did his part to bring eastern civilization to the West.

In 1856, during another trip to the upper Missouri River, the Steamboat Arabia suffered the same fate as the Australia. Hitting a snag near Parkville, Missouri, she sank. In her hold was an unbelievable amount of goods destined for settlements on the Missouri and other military posts. In 1989 the contents were salvaged by River Salvage, Inc. The 200-ton collection of mostly merchandise is on exhibit at "Treasures of the Steamboat Arabia," in Kansas City, Missouri. These artifacts are prime examples of the type of goods that Atkinson would have sold at Fort Pierre. This article will be expanded on in a future publication on the history of the Arabia and her artifacts.

Notes

1. Francis A. Lord, Civil War Sutlers and Their Wares (New York: Thomas

Yoseloff, 1969), 39.

2. Mercantile Library, St. Louis, "Papers of the St. Louis Fur Trade: Robert

Campbell Family Collection," part 3, reel 5, 220-221. Note: The Arabia

Steamboat Museum has boots from J .S. Watson in its collection.

3. Turnley noted, "Officers entitled to quarters at Fort Pierre for 2nd US

Infantry: Col. Montgomery 4, Major Gaines 4, Wessells 3, Lovell 3,

Davidson 3, Lyons 3, Madison 3, Magruder 3, Gardner 3, McLean 2,

Wright 2, Smith 2, Curtiss 2, O’Connel 2, Lang 2. For Commanding

Officer’s Office 1, Paymaster Office 1, Sweeny 2, Turnley 3, Office 1 =

49." The numbers of buildings assigned are given after each officer’s

name. "Fort Pierre," entry 225, Consolidated Correspondence File, Office

of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92, National Archives,

Washington (hereafter cited as RG 92, NA).

4. Letters Received, 1853-1861, entry 225,`part 1, box 2, Department of the

West, 1853-1861, U.S. Continental Commands, 1821-1920, Record Group 393, NA. Proceeding at Ft. Laramie, Nebraska Territory, 2 April 1855, Council of Administration convened to tariff the Sutler Goods. As mentioned in the text; this list was the result of a general order. It was well known that the Indian traders were charging up to 100% markup on goods such as coffee and sugar. This order was based on paragraph 254, which intended to give the posts the power of establishing a tariff of prices to

protect the interest of the soldiers. Each post had to individually assess the

fair cost of articles based on the amount of its actual cost and the

transportation costs. See also Book 2, 9 July 1854 to 18 October 1855, entry 1065, 2nd Infantry, Orders Received/Sent, Record Group 391, NA.

In regard to the sutlery inventory for Fort Pierre, Order no. 70, beef was

also rationed by the sutlery, but the list does not include this item because .

the cattle had not yet arrived.

5. Augustus Meyers, Ten Years in the Ranks of the U.S. Army (New York:

Stirling Press, 1914). This is the memoir of a soldier in the 2nd U.S.

Infantry. His descriptions are especially good for day-to-day activities

from Carlisle, Pennsylvania through the Civil War. See also "Fort Pierre,"

"Fort Levinworth" and "Carlisle Barracks," entry 225, RG 92, NA.

0 comments:

Post a Comment